When Katie Freytag won the Sheridan Prize in 1981 in Gene Trepte’s Invader, she was 22, fresh out of college, and had a sailing resume packed with racing aboard X-boats, M16s, M20s, E-Scows, and Class A. Katie had also been an instructor for two seasons at the Geneva Lake Sailing School and had just completed a summer as head instructor at Delavan. “I was not a regular crew on Invader but just stepped on for that race,” she said of the 1981 Sheridan. Also on board were co-owner John Porter (who had won the Sheridan on Invader in 1980), his brother Brian, Katie’s brothers Billy and T, and John Kiefer. “Why don’t you steer,” John Porter said to Katie, and so she did, from start to first-place finish in the three-boat fleet. The only other woman to have her name engraved on the Sheridan Prize is Miss C. L. Ford, who was the owner of the sandbagger Geneva, the winner in 1879. Her skipper’s name was not recorded.

When Katie Freytag won the Sheridan Prize in 1981 in Gene Trepte’s Invader, she was 22, fresh out of college, and had a sailing resume packed with racing aboard X-boats, M16s, M20s, E-Scows, and Class A. Katie had also been an instructor for two seasons at the Geneva Lake Sailing School and had just completed a summer as head instructor at Delavan. “I was not a regular crew on Invader but just stepped on for that race,” she said of the 1981 Sheridan. Also on board were co-owner John Porter (who had won the Sheridan on Invader in 1980), his brother Brian, Katie’s brothers Billy and T, and John Kiefer. “Why don’t you steer,” John Porter said to Katie, and so she did, from start to first-place finish in the three-boat fleet. The only other woman to have her name engraved on the Sheridan Prize is Miss C. L. Ford, who was the owner of the sandbagger Geneva, the winner in 1879. Her skipper’s name was not recorded.

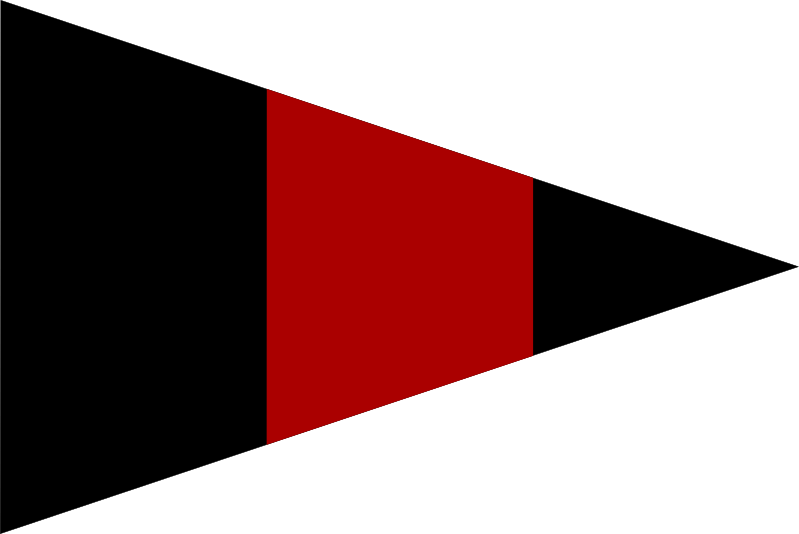

The trophy for winning the Sheridan is called the Sheridan Prize, and at first it was to be a silver cup. After further thought, however, those in charge opted for something unusual, even though they had to wait more than a year for it, and they commissioned Chicago silversmiths Giles, Brother & Company to design and produce a sterling silver 10-inch model of Julian S. Rumsey’s topsail sloop Nettie, the 21-foot sandbagger that won the 1874 race on corrected time over six other boats. The detail on the model is remarkable. Notice the filigree reef points, the tiny blocks and mast hoops, the perfect cleats, and the blue rectangular “Champion” flag on a staff at the masthead. (A photograph in the1913 Sheridan Race program shows Nettie also flying Old Glory from a flag halyard at her mainsail leech.) The Nettie sits on a flat oval surface engraved with the names of winners through 1884. Names through 1933 are engraved on a larger flat oval surface set on a black wooden base. In between these two surfaces, probably added along with the glass dome soon after the second surface was filled up in 1933, are four silver bands that are attached in vertical rows to an oval core. (Katie’s name is engraved on the third silver band.) After the 2008 race, the engraver filled the final space on the fourth band, and since then the winners’ names have been recorded on a wooden plaque, decorated with a drawing of Nettie flying the LGYC burgee. The winner may keep the plaque until the following year.

The Sheridan Race, described in a Chicago newspaper in the late 1800s as “an event of great social magnitude,” has a rich history and has generated colorful prose. A reporter for the Chicago Herald in 1892 wrote as follows: “The race was as pretty as any that imagination could picture, and was seen almost from start to finish by hundreds of persons on the thirty-odd little steamers, on sailboats, or on the piers and landings. Scores of folk came from the country round about to witness the contest, and at times the waves of excitement were far higher than the sea.”

The event also has its share of anecdotes. Is it true that General Philip H. Sheridan came to the Geneva Lake area in 1874 to fish, not to watch boats race? Yes. Is it true that John Beamsley’s local bottling company changed its name in 1875 to Sheridan Springs Mineral Water in honor of General Sheridan, who had praised it, and that a former LGYC commodore has one of those old bottles in her collection? Yes. Is it true that the Civil War bugler who was the first person to play Taps (1862), settled in Chicago and won the Sheridan Prize in 1892? Yes. Is it true that Class E replaced Class A in Sheridan competition for four years in the 1970s? Yes. Is it possible that your name is engraved on the Sheridan Prize or the Sheridan Plaque? Yes, it is possible, but click here to find out.